Being an artist or composer perceived to challenge the doctrinal orthodoxy of Stalin’s “socialist realism” in Russia in the 1930s, was to play a very dangerous game with the capriciousness of fate.

Little wonder Shostakovich lived in constant fear of arbitrary arrest – sleeping in the stairwell of his block of flats, a small suitcase by his side to hold the few belongings he would be able to take with him to what dissident writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn called ‘The Gulag Archipelago’.

Sergei Prokofiev knew the feeling well. By the time he composed the ballet score to ‘Romeo and Juliet’ in 1935, the wheels of Stalin’s ‘Great Purge’ were beginning to gain traction. A decade or so later the musical doctrine initiated by Andrei Zhdanov against composers who displayed ‘formalism’ came into full force.

It may well explain then why his ‘drambalet’, which was first written with a ‘happy ending’ in 1935, was revised to reflect Shakespeare’s original tragedy by the time it was heard again in 1940.

Midnight knock

It was well known that Stalin would write either ‘good’, ‘average’ or ‘rubbish’ on the sleeve of recordings sent to him to listen to.

Being linked to Shostakovich as a ‘degenerate modernist’ in the newspaper Pravda in 1936 would have certainty shortened the odds of hearing the dreaded midnight knock on the door and being given a one-way ticket to Siberian oblivion.

It was well known that Stalin would write either ‘good’, ‘average’ or ‘rubbish’ on the sleeve of recordings sent to him to listen to.

Fate beyond control

Thankully for Prokofiev, the significantly revised 1940 version was a success (gaining a Stalin Prize), although he was unhappy that his score had been amended by choreographer Leonid Lavrovsky.

However, like Romeo and Juliet, fate was beyond control – in Prokofiev’s case (left - below), even in death. His health long since broken, he had to balance the award of six Stalin music prizes against his first wife being sentenced to 20 years hard labour.

‘Never was a story of more woe’ to ring truer.

A true man of steel and one with a heart of stone...

He died on the same day as Stalin; the funeral held at the same time in Moscow. His coffin was passed by hand against the throng of the crowds to the cemetery. Shostakovich was one of the few people by the graveside.

It adds a cruel twist to the legacy of a work that is now universally loved, even if many of its subsequent productions (the British choreographer Matthew Bourne set it in a mental hospital) would have sent old Joseph Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili spinning in socialist realism apoplexy in his mausoleum in Red Square. Prokofiev had the posthumous last laugh.

He died on the same day as Stalin; the funeral held at the same time in Moscow. His coffin was passed by hand against the throng of the crowds to the cemetery. Shostakovich was one of the few people by the graveside.

Reinvented in spirit

The 1940 score has remained a constant – filled with its hallmark juxtapositions of love and hate, naivety and wisdom, drama and pathos, each illuminated through his specific scoring and dissonant harmonic techniques that he felt had almost been lost through his early tuition under composer Glière.

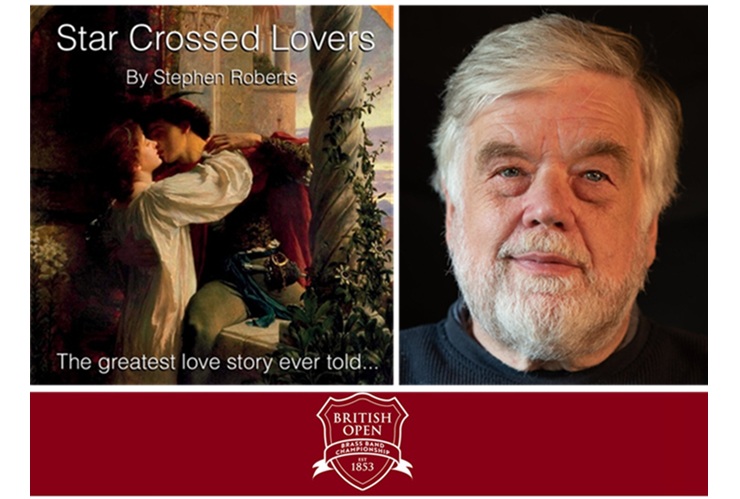

These have also been explored and exploited, revised and reinvented in spirit by composer Stephen Roberts to form the basis for ‘Star Crossed Lovers’.

So much so in fact that (as with the original ballet) it deliberately ends in triumphant fashion – an exultant climax that reflects the eternal power of incorruptible love, rather than a mix up over a sleeping drug and a handily placed dagger.

No quiet ending

That may irk the Shakespearean scholars (and possibly an old Marxist or two) in the audience at Symphony Hall, but as for the hardnosed contest goers, the composer says, he believes “it is true to say that quiet endings do not suit competitions”.

That may irk the Shakespearean scholars (and possibly an old Marxist or two) in the audience at Symphony Hall

They won’t be too bothered either that it doesn’t follow Shakespeare’s plot either (there is no balcony scene) – the 16-and-a-half-minute work more a collection of character highlights and motifs rather than linear narrative journey.

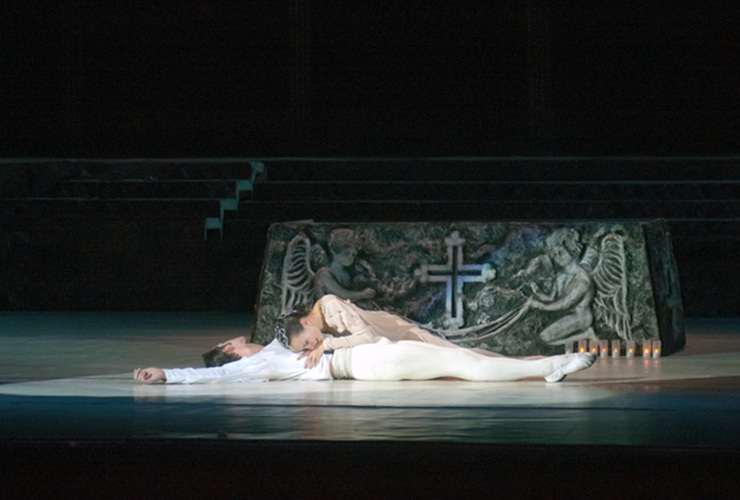

Embraced in death...

Tension

What it does resonate with though is the same sense of underlying tension (mirroring Prokofiev’s scoring techniques), as the opposing factions of the Montagues and Capulets and their two naive minded teenagers (Romeo is 16, Juliet just 13) are defined by the very nature of their impulsiveness and passion.

It is music that the composer draws with great melodic assuredness and sharp-edged characterisation; interspersing the familiar and not so familiar elements of Prokofiev with his own neatly observed cameo portraiture – right from the sliding chords of the opening bars that hint of the dark drama that is about to unfold.

The liberamente duet cadenza that follows introduces our star-crossed lovers – the tubas quietly positioned in the dark recesses below the stave like heavies with hidden stilettos in their pockets.

The liberamente duet cadenza that follows introduces our star-crossed lovers – the tubas quietly positioned in the dark recesses below the stave like heavies with hidden stilettos in their pockets.

Character vignettes

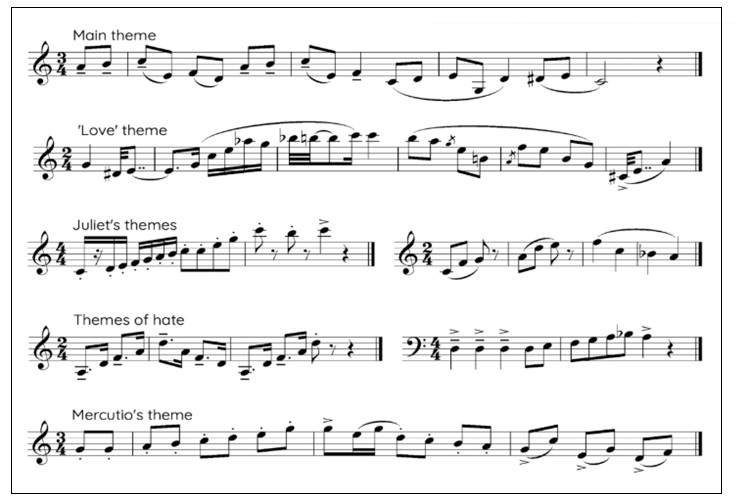

Thereafter, the character vignettes and themes (below) are drawn together like dancers popping from behind the drapes to steal their moment in the spotlight - although not in quite the same order as the ballet.

Sometimes it occurs fleetingly (as in the Furioso that follows), at another time out of sight (with the offstage cadenza group of cornet, flugel, horn, baritone and trombone) or full centre-stage gaze (euphoniums). The pulse has a contemporary balletic feel – strict, but with hints of the angular jazz movements brought to life by choreographer Jerome Robbins in 'West Side Story'.

Effervescent spirit

Juliet is an effervescent spirit; a running, skipping, quick witted, headstrong whiplash of teenage naivety. Romeo on the other hand seems a more hopelessly romantic figure.

The actual catalyst for both trouble and tragedy in the score is the virtuosic figure of Mercutio, as brave as he is foolhardy in being killed by Tyblat, who Romeo then slays in a fit of anger.

The centrepiece masked ball showdown with its famous ‘Dance of the Knights’ theme is heard like a leitmotif throughout – a brooding, inky-dark portent led by a bass trombone that treads a fine line between Sydney Greenstreet menace and a malevolent goose.

The centrepiece masked ball showdown with its famous ‘Dance of the Knights’ theme is heard like a leitmotif throughout– a brooding, inky-dark portent led by a bass trombone that treads a fine line between Sydney Greenstreet menace and a malevolent goose.

There is also a breathless testosterone fuelled running battle between the family gangs and their supporting confederates through the streets of Verona - like the Palio di Siena horse race with ballet dancer jockeys on board.

Denuoement

However, the denouement, built on misunderstanding and miscommunication is drawn out on the broadest of canvases.

Get it right though and even in death there will be a happy ending for at least one band.

And whilst the audience already knows of the fate that befalls the young lovers, it will take a determined conductor/director to get to the end without losing the required sense of dramatic impulse after the solo cornet declares his undying love one last time before heading to the crypt.

It's a thickly scored ending – a soaring melodic lead underpinned by intensive filigree work that even with the best will in the world sees our ‘Star Crossed Lovers’ taking their time to take a sip of the Shakespearean ‘Kool-Aid’ and commit hara-kiri.

Get it right though and even in death there will be a happy ending for at least one band.

Iwan Fox