The 1970s - The decline and fall of Belle Vue & the British Open

15-Jul-2010Iwan Fox looks back at a decade that started with such hopes for the iconic contest but almost ended up like the last elephant at its famous zoo - dead and buried.

Entering its death throes: The King's Hall in the 1970s

The decade of the 1970s, that started with such hope and aspiration, ended in almost farcical despair, as Britain lurched towards its post war nadir, as a country regulated by Keynsian economic consensus and Beveridge inspired welfare reform finally succumbed to the growing appetite for consumerism and self interest.

And Belle Vue, home to the iconic British Open Brass Band Championship, mirrored the decline in full.

Victorian splendour

Victorian splendour

In the months leading up to the first ‘Open’ of the new decade (1970 programme right), Belle Vue still advertised itself with the promise of extravagant Victorian splendour.

A new ‘Tropical River House’ had been built at a cost of £65,000, the Zoo boasted ‘Big Cats’, ‘Bear Pits’ and a ‘Penguinarium’, there was a ‘Great Train Robbery’ exhibition, weekly wrestling, speedway, stock cars and nightly dancing.

Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones did gigs at the huge King’s Hall, and although the ‘Mammoth Midget’s Circus’ featuring a host of ‘The Cleverest Little People’ had ended some years before, in a strange coincidence, one of the last pantomimes to be staged was ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’.

By the decade’s close, almost all of it was gone.

Demolished

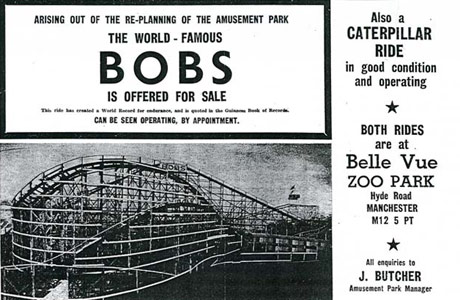

The famous ‘Bobs’ racers were demolished in 1971, followed by the circus, the railway and the Zoo in 1977. The Gardens, the bedrock attraction since 1834, lasted just a couple of years into the 1980s.

The King’s Hall was just about the last thing left standing.

The lack of investment in an attraction that had long since passed its sell by date was obvious, even to those with the deepest hued rose tinted spectacles.

The end of the Bobs: By 1971 the famous ride was gone

Fight

Phil Blinkhorn was the Sales Manager in the late seventies: “You had to fight to get anything from the owners Trust House Forte. The place needed huge sums to be invested, but despite the talk of turning the place into a conference and exhibition complex, nothing ever came of it – and then it was too late.”

With the advent of cheap holiday flights, an increase in social mobility and that growing consumer desire for change, an increasingly decrepit Belle Vue saw time pass it by.

However, even in its own death throes, the British Open still managed to produce the occasional emotional spasm of controversy to course through its veins, such as the furore over the selection of Elgar Howarth’s ‘Fireworks’ in 1975.

People still made the trip to the contest, although more as a pilgrimage than anything else. The claims that there were audiences of 5,000 or more for the British Open were made with a touch of bravura salesmanship however.

Numbers down

Numbers down

By the late 1970’s numbers were down and falling fast, and not just because new plastic seating had been put in around the central ring (although the wooden plank seating in the other areas remained).

The problem was that the British Open of the 1970s was very much the British Open of the 1950s – from the dated adverts in the programme (which cost a shilling in 1970 and 25p by 1979), to the call to join the National Brass Band Club and the Festival Concerts with massed bands and ‘star’ singers from the radio.

Forget Jimmy Page and Robert Plant, Mick and Keith - the Open Festival Concerts offered Madge Stephens and Ian Wallace (right).

The rough edges, peeling paintwork and chronic lack of investment in both the contest and its host were beginning to show through.

Pontins

Despite the first prize rising from £200 to £650 by the decade’s end (including the change to decimalisation in 1972), the tired prizes seemed to mirror those found on the Saturday night ‘Generation Game’, hosted by Bruce Forsyth: a watch metronome, executive briefcase, gallery tray and goblets, parcels of music.

The fledging Pontins Contest advertised itself in the 1976 programme with the promise of ‘the largest cash prizes ever offered for a brass band championship’.

Top prize at the bandsman’s ‘holiday weekend’ in Prestatyn was £750. Even the winners of the Third Section there would take home more than the £250 on offer at the Open.

Elsie Tanner

Nothing had moved on (there were better prizes to be won at the contest 40 years before) – even a desperately cheap promotional shot at the time featured ‘glamour puss’ Elsie Tanner from Coronation Street (below right) looking like she was on the pick up outside the sign for the elephant rides.

The King’s Hall, once the jewel in brass band contesting crown, had become a shabby, tired and inappropriate venue – a conflagration waiting to happen.

How it was for the bands: Besses on stage

Fires

Two extensive fires at Belle Vue in the previous 12 years had been warning calls, whilst the growing public concerns over potential IRA attacks (and there was an evacuation at the contest itself in 1978) also highlighted its health & safety shortcomings, despite an effective fire safety procedure.

Built in the 1920’s the hall was nearly all made of wood, it’s roof supported by steel columns. From the main foyer on its east side was the crush bar and manager’s office and straight ahead the auditorium, with stairs to upper tiers left and right.

Underneath the hall ran tunnels to connect to the west side of the complex; above, a hospitality suite, with it’s infamous sloping floor; to the other side, the artists dressing rooms, behind them, and to the rear, the clutch of small outlets to sell candy floss and sweets, and cages for the more dangerous circus animals.

Packed to its rafters though, it still hummed with humanity. The trouble was, it wasn’t getting packed often enough, despite the Masonic meetings, circus and pop concerts.

Oblivious

Oblivious

With the 118th British Open in 1970, the contest entered its last complete decade of life, oblivious to what lay ahead.

By the time of the 127th running in 1979, even the ornate programme cover was being printed for the last time (replaced from 1980 to 1984 by garish ‘Daily Mirror’ art work), famous names had disappeared and the contest faced an uncertain future.

Jack Fernley, the respected administrator passed the organisation of the contest over in 1970 (retiring as General Manger in 1973), and the Iles family connection ended with the death of ‘Eric’ Iles in 1971.

And despite the Brass Band office still packed with mementos and memorabilia above Caesar’s Palace, it was revealed by Harry Mortimer in 1977 that the General Manager Christopher Hind was allowing the contest to retain the wonderful £2,000 Gold Challenge Trophy, as running of the contest passed to him.

Everything was changing.

Last Mortimer

The last Mortimer name appeared on the list of competing bands in 1974, whilst former winning conductors such as Jack Atherton, Stanley Boddington and George Thompson made their final appearances too.

Others of course replaced them, including debuts for future winners Peter Parkes, Frank Renton and Bram Tovey, whilst Betty Anderson became the first woman to conduct at the contest and other interesting names such as Elgar Howarth and Howard Snell made their first fleeting appearances.

Borrowed time

Some bands were living on borrowed time and the remnants of a bygone age, whilst others started to make their first impressions at the highest level – including the Skellerup Woolston Band from New Zealand, which appeared and surprised many, by coming 5th in 1975.

Yorkshire dominated (18 out of the 30 podium places in the decade were won by bands from the county), and with the exception of the wins from Brighouse and Wingates, sponsored outfits (Black Dyke, Yorkshire Imps, Fairey) had a stranglehold on the prizes.

After the politically inspired Miners industrial victories of 1972 and 1974, colliery and mining community based bands were regular contenders. It was to be their last rallying call.

Still excite

The contest did still manage to excite as well as rile the senses and opinions however – from the repositioning of the adjudicators box in 1970 to the choice of ‘Fireworks’ as the set work in 1975, Black Dyke’s thwarted attempt to complete a historic double hat trick in 1978 and the added attraction of Granada Band of the Year.

The reality though was that the Open was on its last legs, even though a subservient banding press seemed oblivious to the winds of change or unwilling to make critical comment.

Stench of decay

By 1979 the stench of decay had become unmistakable (Shirley Bassey said it smelt like an animal house). There was also a growing feeling that the running of the contest had started to smell fishy too.

For all of his passion and commitment to keeping the British Open as the foremost brass band contest in the world, Harry Mortimer’s involvement after the death of Iles became increasingly paternalistic.

The end: Jennisons, and the Slot Palace stand waiting for the wreckers ball

Name alone

Famous bands with poor recent records seemed to be holding their place at the contest by virtue of name alone, and the full results of the contest were not published. There was a feeling of nepotism at work and many a less ‘famous’ band was at times treated shamefully.

Three Grand Shield winners were given just one opportunity at the contest, another just two years.

Test piece choices became increasingly conservative too after the Fireworks explosion of 1975, the choice of judges seemed prescriptive.

For its 125th anniversary in 1977 (‘the next great brass band milestone’ as he described it), Mortimer looked back and not forward and picked ‘Epic Symphony’ as the set work

Closed Shop

Closed Shop

The Open began to lose its allure amidst the patina of the pungent damp and encrusted dust of the King’s Hall. The contest was starting to resemble a brass band version of that most damaging of 1970s industrial phenomena – the ‘Closed Shop’.

If it couldn’t contemplate change, the writing was on the wall.

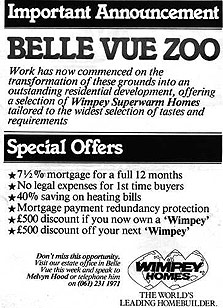

There was still hope if Belle Vue itself could be resurrected, but nothing materialised, and the first nails in the coffin were hammered in 1977 when the decision to build the eventual G Mex centre was taken by the city and county councils.

Ellie May

There were plans and ideas, small experiments and limited promotions for Belle Vue - but they all came to nothing.

At the end of 1979, the future for the British Open looked just as bleak as that for Ellie May, the last elephant to remain at the Belle Vue Zoo.

Unable to find a buyer willing to house her in the UK, she was left to wander her compound, a symbol of past glory, stubbornly refusing to contemplate a new future away from her home.

She was shot dead to put her out of her misery.

Close thing

Within a couple of years, Belle Vue would suffer the same fate (turned into Wimpey Housing right) , the next cartridge in the extinction gun seemingly having the Open’s name engraved on it.

The 1980s would bring the ‘Thatcher Revolution’ of undiluted self interest and consumer choice. The British Open had to contemplate change or die.

Luckily it chose the former rather than roll over with its legs in the air like poor Ellie May.

It was a close thing run thing however.

Iwan Fox

The author would like to acknowledge the contribution and images provided by David Boardman and Phil Blinkhorn

Please visit:

manchesterhistory.net/bellevue/history.html

Further articles can by Tim Mutum on 4BR at:

www.4barsrest.com/articles/2008/art890c.asp

No images can be reproduced without prior permission being granted.